1. Breaking Barriers

Read how WWF-Russia removed barbed wire at Russia-Mongolian border for free migration of snow leopard and wild ungulate.

Political borders are for people. But for an animal like the snow leopard, with a home range that can be as large as 2,000 km2, barbed wire fences marking country borders are nothing more than an obstacle to free movement.

The fence line, which was installed in Russia along the Russian-Mongolian border in the late 1980s, has been affecting animals including the Altai mountain sheep and Siberian ibex as well. These ungulates, which are the main prey for the snow leopard, try to cross through the barbed wire, get entangled and injured in the process and often die.

With ample evidence of the snow leopard and its prey in this transboundary area, WWF teams in Russia and Mongolia started lobbying their governments to remove the fences.

“Over 30 years, the wooden pillars of the fence have partially rotted, and the barbed wire simply lies on the ground, which poses a danger both for wild animals that traditionally migrate over the territory of the Ukok plateau, and for domestic animals that graze there,” says Aydar Oynoshev, Director of the Directorate of protected areas of the Republic of Altai.

WWF-Russia and WWF-Mongolia continued making appeals to the governments of the two countries with a request to dismantle the barriers at the most key sites for the migration of wildlife, citing the results of wildlife tracking using radio collars and evidence from camera traps.

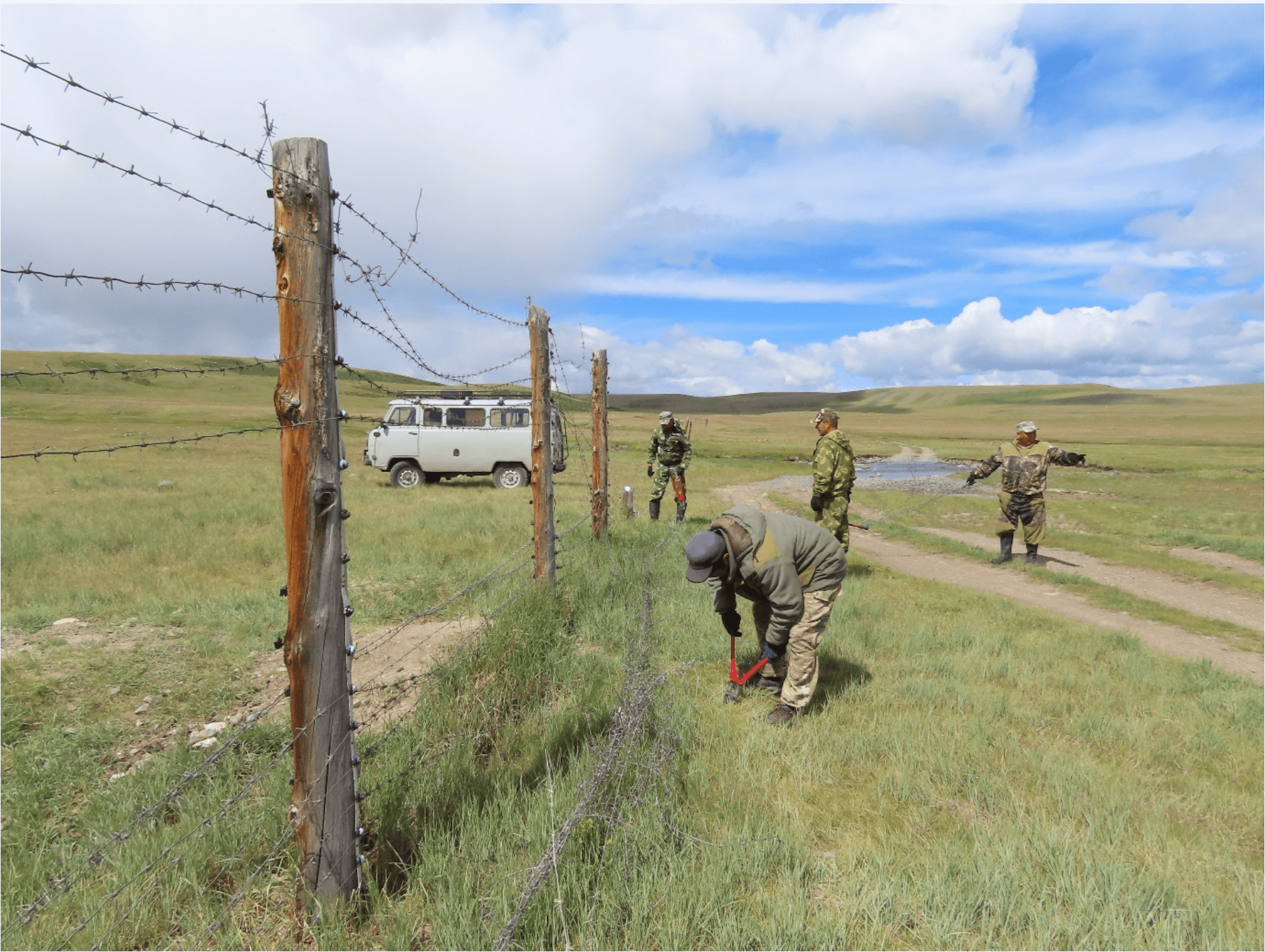

After years of lobbying, the work of the WWF teams finally bore fruit and in June 2020 the process of removing the fence started. Eight kilometers of unused fences on the border with Mongolia and Russia were dismantled in the Republic of Altai on the Ukok plateau.

The barbed wire was removed by rangers of the Directorate of Protected Areas of the Republic of Altai, who manually dismantled the wire, transported it by car to the place where a hydraulic press-machine was installed. The press-machine helped compress the wire, which made it easier to load it onto a truck and taken out from the remote territory of the Ukok plateau. With the work on removing the fence already in motion, there are plans to completely dismantle and remove unused fences from the entire territory of the Ukok Quiet Zone Nature Park.

Removal went on in summer of 2021. Dismantling of barbed wire was approved by the Border Service of the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation, the rangers of the Directorate of Protected Areas will be working for several weeks to remove the wire and old poles on a remote area of high biodiversity. The project was supported by WWF and World Around You Foundation of Siberian Wellness, a Russian corporate donor.

Totally in 2020 – 2021 the rangers removed 22 km of old non-used barbed wire fences and rotten wooden poles to save animals from dying of tangling in the barbed wire while migrating.

“The snow leopard subpopulation in high mountain area of Ukok Plateau is transboundary, so all wildlife constantly crosses the border and barbed wire impeded it. It’s a big success of the snow leopard conservation, we removed these constraints and have created conditions for freely gene flow of the snow leopard between Russian and Mongolian parts of Tavan Bogd mountain. Next year we are going to conduct transboundary snow leopard survey using camera traps and find out more about this subpopulation”, said Alexander Karnaukhov.

Today wild animals, such as the Altai mountain sheep, Siberian ibex and the snow leopard, can migrate freely from one country to another.

“Lockdown has shown us more tangibly than ever before how difficult life can be when we are not able to move,” said Wendy Elliott, Deputy Lead Wildlife Practice, WWF International. “This is what animals face all over the world when their habitats are fragmented into ever smaller ‘islands’, or their movement pathways are blocked by fencing, roads or railway lines. This remarkable removal of border fences will feel to the wildlife of the area much like the opening of lockdown did for us.”

WWF teams will soon install camera traps in the Ukok plateau and will continue to use the photos and videos captured to develop a better understanding of the enigmatic wildlife of these high mountains, and to document how free movement helps these populations thrive.

2. Spotty nomads

WWF-Russia proved snow leopard migration long distances across the border of Russia and Mongolia

WWF Russia and WWF-Mongolia received the first ever video and photo-confirmation that snow leopards inhabit the Mongolian side of the Ikh Soyon ridge in Khuvsgul aimag (province). There are two snow leopards captured by camera in Ikh Soyon ridge in Mongolian side. Both individuals were confirmed by WWF Russia and WWF-Mongolia experts as well-known males that WWF has been following for ages on a Russian side of the ridge.

Snow leopards live and roam across large swathes of interconnected landscapes of Asia’s High mountains in 12 range countries. Incredibly well camouflaged and rarely seen in the wild, not much is known about them and research is scarce. Scientists rely on camera traps and telemetry to understand their home ranges, their behavior and estimate of how many exist in an area, which helps conservationists develop strategies to protect them.

It was one of these camera traps, installed in Eastern Sayan, that captured the first evidence of the snow leopard in 2014 in the transboundary area across the Mongolia -Russia border. The camera trap captured a male snow leopard called Munko – initially captured by camera trap in Russia and later photographed in Mongolia.

For solitary and nomadic snow leopards, travelling large distances is not unusual. But travelling across such large distance is not always easy. Some of the snow leopard range countries have volatile border situations. But even without clashes, political boundaries are often marked with fences, which restrict movement of snow leopards like Munko and other animals.

“The video and photo confirmation of the snow leopards migrating from Russia to Mongolia and back is extremely important. It proves the importance to collaboration between both countries on scientific and governmental level to save the globally endangered species like snow leopard. The Eastern Sayan population of snow leopards in the transboundary zone of Russia and Mongolia is the only population, which portion in Mongolia totally depends on Russian animals, it’s a very isolated snow leopard population from a core snow leopard habitat”, says Alexander Karnaukhov, Senior Coordinator, Altai-Sayan Branch of WWF Russia.

“The camera traps helped us understand that the Eastern Sayan population of snow leopards, in the transboundary zone of Russia and Mongolia, is the only population where the number of snow leopards in the Mongolian part of the habitat are less than the Russian part. This means that the snow leopards in Mongolia need to move across to Russia to hunt and mate and need a free corridor to move,” added Alexander.

One of the snow leopards registered on Mongolian side of the ridge by cameras turned out to be “Russian” individual that WWF Russia has been observing for years. It’s a male called Munko after the name of Munku-Sardyk (Mong. Munkh Saridag) mountain ridge the individual inhabits, the border area between Russia and Mongolia. This year Munko was the first snow leopard in Russia whose mating call was recorded by WWF. Munko is a strong dominant male in his area. Another one is a snow leopard male called Champion (named by local people after the local sports champion).

Assessment of current status and identification of snow leopards in the Russian-Mongolian border areas is implemented within the frames of the Project “Transboundary cooperation on the conservation of Amur tigers, Amur leopards and Snow leopards in North-East Asia” funded by North-East Asian Subregional Programme for Environmental Cooperation (NEASPEC) in Russia. It is also implemented within the Nationwide Snow leopard population assessment in Mongolia funded by WWF-Netherlands, WWF-Germany and WWF-US.

3. The Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation officially approved the snow leopard monitoring programme developed by WWF Russia

It is a huge success for snow leopard conservation. Only the Amur tiger, the second big cat species of Russia, has had the monitoring programme approved by the Ministry of Natural Resources. Today the snow leopard has finally gained the basics for state support and enhancing in the field of species monitoring and conservation.

“The snow leopard monitoring programme was developed by WWF Russia and conservation partners in 2016 and first presented the monitoring programe in GSLEP forum in 2017. Since them even other snow leopard habitats got interested in monitoring programme: Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, but until October, 2021, the program stayed unofficial within the country”, says Alexander Karnaukhov, Senior Coordinator of Altai-Sayan Branch of WWF Russia.

Official approval of the snow leopard monitoring programme by the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation provides the obligation to all state governed Protected Areas to follow the principle of the unified methodology while surveying the snow leopard. As PAs are key partners of WWF in snow leopard conservation in Russia it will provide for the unified approach to data collecting and processing, reliable and comparable data on snow leopard distribution and numbers through all habitats in the country.

“It is hard to underestimate this decision as WWF has been trying hard for 3 years to propose and advocate to the Ministry of Natural Resources for the unified, scientifically based approach to snow leopard survey and monitoring. Today snow leopard conservation in Russia has risen up to the next level.

Today WWF Russia is the lead organization on snow leopard conservation in Russia supported and coordinated almost all activities on monitoring and conservation of this illusive cat.